If you want to control maritime traffic among the most populous nations on earth, you have to control the South China Sea. Over one-third of all global shipping passes through the South China Sea, transporting raw materials, fuel, and manufactured goods to and from the great economies of Asia: China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan. The South China Sea is also resource rich, with abundant fisheries and vast reserves of oil and gas waiting to be tapped beneath its shallow waters.

On the surface of the new world of the 21st century, the eighth continent, otherwise known as the moon, there is another area of even greater strategic significance than the South China Sea—the water-rich polar regions of the moon. Controlling this portion of the lunar surface could be a prerequisite to more quickly establishing a permanent presence in space. Confirmed less than a year ago, these water resources are frozen in the shadows of the craters, especially around the lunar south pole.

Much has been made of the potential for humans to colonize Mars. With abundant water, a thin atmosphere, a 25-hour day, and mineral resources, it certainly is feasible to eventually colonize Mars. But in our enthusiasm to launch a Mars mission, we risk overlooking the strategic imperative to establish bases that can access water resources on the moon. Here are some benefits of such a moon base:

- Only four days from Earth versus a minimum of 90 days to reach Mars.

- Only one-sixth of Earth’s gravity versus Mars having one-third Earth’s gravity, meaning far less fuel required to lift payloads off the lunar surface.

- No atmosphere, meaning landing on the lunar surface requires less complex spacecraft engineering and less maneuvering payload.

- Strategically located with military benefits including a platform to launch killer satellites in retrograde orbits around Earth.

- Land based which creates the ability to establish a harder target, far less vulnerable to attack compared to space stations orbiting Earth or the Moon.

- Water and minerals sufficient to generate habitat atmosphere, rocket fuel, and raw materials for base infrastructure.

- By virtue of the polar location, it is possible to set up solar power collectors on the lunar peaks that can generate continuous power.

- Capable of becoming a self-sufficient base from which to provision and launch robotic mining expeditions to asteroids, as well as shipping lunar-sourced finished goods back to Earth or to build a Mars colony.

- Potential to become a source of materials with which to build satellite solar power stations in Earth orbit, along with limitless other manufacturing possibilities.

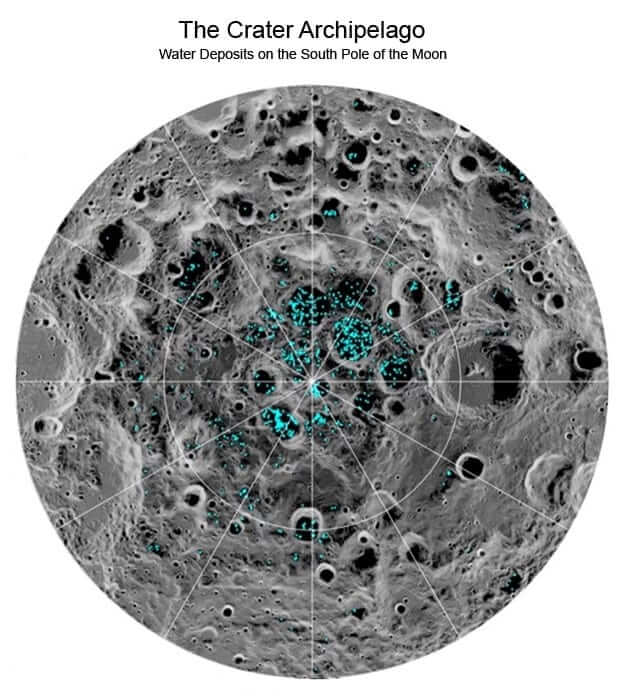

Where the South China Sea has strategic archipelagos of islands, the polar regions of the Moon have strategic archipelagos of water rich craters. Principle among these, with the lunar south pole forming a bullseye almost dead center inside of it, is the Shackleton Crater, named after Ernest Shackleton, the first human to explore Antarctica. Sprinkled around Shackleton are other strategic craters, Sverdrup, Haworth, Shoemaker, and Faustini.

As the image below shows, surface ice is concentrated at the moon’s south pole. Because portions of the craters in the moon’s polar regions are in permanent shadow, ice is able to form without getting burned off. Surface ice has also been detected on the moon’s north pole, although surveys so far show much less of it by comparison.

When talking about strategic risks and opportunities, it is important not to get mired in the technology of our time and ignore the unknown unknowns, those unforeseeable technological breakthroughs that will leapfrog existing economic and military barriers. The islands of the South China Sea are now fortresses, occupied by the Chinese military. But these fortresses cannot withstand a surgical strike using hypersonic projectiles, or particle beams, or a swarm of attack drones, much less from systems we can’t yet imagine.

Nevertheless, possession is nine-tenths of the law. The Law of the Sea, much like the laws and treaties currently governing development in outer space, is just words. When an international tribunal at The Hague ruled against China in 2016 in a dispute over its illegal occupation of the islands of the South China Sea, the Chinese shrugged their shoulders, and deployed another missile battery.

Notwithstanding technological breakthroughs that surely will occur in the next 50 years, the presence of water on the moon means that the primary resources necessary for rocket fuel, along with water and atmosphere for human habitats, do not have to be lifted off of earth. In the here and now, these craters have compelling strategic value.

Not only is the south pole of the moon a strategic site because of its water resources and potential to generate uninterruptible solar energy, it is near the location of the Aitken basin, a massive crater stretching 1,240 miles across the far side of the moon. Scientists recently have determined there is a deposit of extremely dense material buried in this crater—possibly the remnants of a massive asteroid that crashed into the moon. The potential mineral riches in this crater offer additional motivation to establish bases on the south pole of the moon.

China has taken notice. It is not a coincidence that their recent, and first, successful Chang’e 4 moon landing was in the center of the Aitken basin, which is only a few hundred miles from the moon’s south pole. China’s not alone. India intends to land a rover on the moon’s south pole this September. Even a private spacefaring company, Blue Origin, owned by Amazon titan Jeff Bezos, has announced its intention to send its Blue Moon lander to the lunar south pole

The technological spin-offs that accrued to America’s space programs of the 20th century are well documented. America’s investments in the Apollo program, in its heyday exactly 50 years ago, hastened the development of the integrated circuit, dramatic advances in rocketry, “remarkable discoveries in civil, electrical, aeronautical and engineering science,” complex software, lightweight and incredibly durable composite materials, and—for a few specifics—everything from CT scanners to liquid-cooled garments to freeze-dried food.

Surely an accelerated program to establish bases on the moon would help ensure American technological preeminence in the 21st century. But that’s not the only reason to do it.

Bases on the south pole of the moon are critical for establishing a military and economic presence in outer space. They are the source of raw materials for exploration further into the solar system; they also constitute the high ground in the great game back here on Earth. NASA has announced plans to send astronauts to the lunar south pole by 2024. Let’s hope that will not be too late.

The space lanes of tomorrow, like the sea lanes of today, will have choke points, ports, supply chains, and trading hubs. The south pole of the moon is the South China Sea of Earth. And just like the South China Sea, it will be stealthily and deceitfully occupied and militarized by a foreign power, a fait accompli, unless we get there first.

Content created by the Center for American Greatness, Inc. is available without charge to any eligible news publisher that can provide a significant audience. For licensing opportunities for our original content, please contact licensing@centerforamericangreatness.com.

Photo Credit: Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty Images